Home » Conservation » Costa Rica’s Legendary Environmentalist: Alcides Parajeles

Called the “peasant environmentalist,” Alcides Parajeles has endured threats, harassment, and in some cases, violence as he voices his concerns of destruction to the natural environment around him. The story reads like an unbelievable soap opera involving organizations meant to help but somehow are ineffective in protecting environmentalists like Parajeles.

Parajeles has dedicated his life to condemning Poaching, trafficking, and illegal logging in the Osa Peninsula region of Costa Rica. Going against poachers and loggers over many years has put him in dangerous situations and has brought unexpected political responses.

Most recently (December 2021), the Costa Rican Federation for the Conservation of the Environment (FECON) sent a message to Andrea Meza, Environment and Energy Minister of Costa Rica, on behalf of Parajeles, hoping to bring some relief from harassment to him and his family.

The message included a reminder that Parajeles received the Guayacan award from the Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE) in 2017. He continues to fight the battle “despite his advanced age and continues to actively fight to denounce hunters, loggers, and traffickers of wild animals in Osa.” (1). The message went on to say that the local National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC) had verbally attacked him and dismissed his complaints.

Meza was also told that Parajeles and his family still receive death threats and are being stalked by hunters. FECON questioned the Minister’s office to better understand why an elderly defender of nature who was in danger and need of support from local SINAC officials was not receiving any help.

But Minister Meza did not acknowledge that she received the message. Those under attack feel a bit of state abandonment after years of sending these pleas for help with no solution.

A big concern is that Parajeles lives and farms among those he is condemning, and they are his neighbors in Pavoncito de Sierpe. Wildlife trafficking is a lucrative business and involves organized crime mafias, making his quest even more dangerous.

Parajeles moved to the mountains when he was four years old. He remembers seeing jaguars, pumas, and other wildlife in abundance. In a story published in La Nacion, Parajeles, now in his 70s, tells a story of how his soul was broken when he saw wild animals machine-gunned because the cats would eat a pig or calf of a rancher. Now the numbers of jaguars and pumas are significantly reduced, not only by slaughter but also for trafficking. (3)

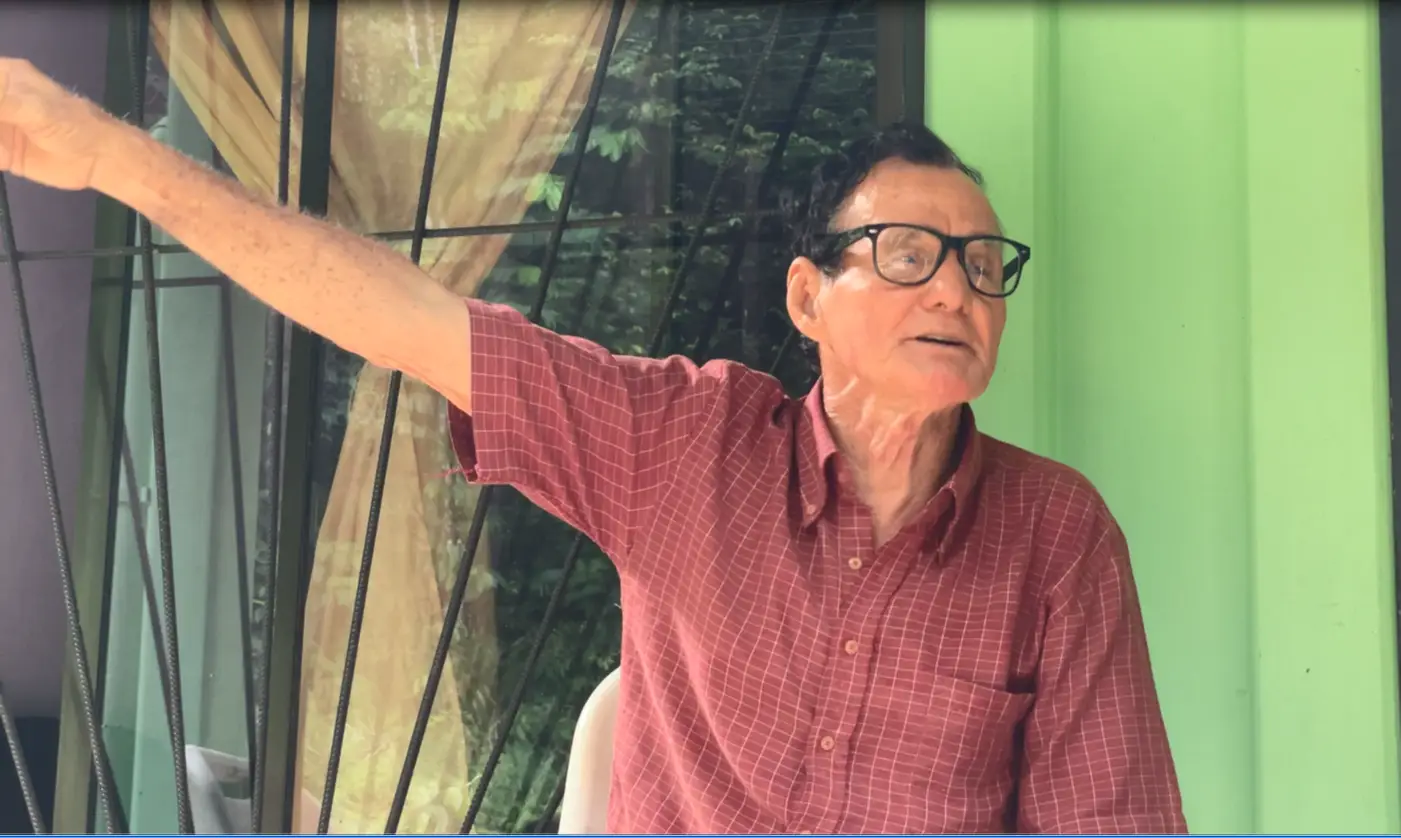

If you pull up a photo of Parajeles, you can see the sadness on his face. His actions prove the love in his heart for his beloved mountain ecosystem and the need to conserve it.

His name is well known in Costa Rican courts, Constitutional Chamber, and the Legislative Assembly, where he denounces illegal hunting and environmental destruction. He also has discovered and denounced government officials for not doing their jobs.

As with all environmentalists, Parajeles is driven to provide a better place for his children and grandchildren. He hopes they will continue the tradition and use what he has taught them about the environment. If these current practices of destruction are not stopped, there will be no nature left for them – not like he once knew.

Parajeles has much knowledge to share and does so freely with researchers, politicians, park rangers, and conservation workers. To go even further, he lends his 600-hectare farm to researchers studying felines in the Osa Peninsula.

Many who have fought for Costa Rican environmental protection became victims of the threats made against them. Let us remember those brave environmentalists:

In the 1990s, threats were constant against many people who denounced environmental damage. Some were writers, journalists, ecologists, and engineers. Ecologists were arrested while peacefully protesting deforestation in the Osa Peninsula. In 2008, residents were threatened in Perla de Guacimo because they complained against water contamination created by pineapple cultivation. (2)

The threats and intimidation continue.

As with many conservation and wilderness protection areas, the region where Parajeles is living does not have enough Park Rangers to patrol and protect the area. In 2018, FECON reported that 800 Park Rangers and equipment are needed to deal with the crisis. Most resources are earmarked for attractions and attention of tourism in the National Parks, not for control and prevention. (4)

FECON claims that the lack of action by the Costa Rican State contributes to global wildlife trafficking, which is fueled by its profitability. It is the third most profitable illegal activity in the world, behind drugs and weapons.

Environmentalists feel defenseless against the industry run by the big-time crime mafia. But they continue to fight, even though their lives are threatened.

Many crimes go unpunished as threats are often delivered in private with no witnesses. Murders of environmentalists, of which have been over a dozen (many unsolved), also go unpunished due to the lack of Park Rangers and legal protection.

These stories are screaming out for the need and urgency of the legal protection of human rights defenders and those defending nature. Let us not forget these protectors of the environment and the tough fight they have been giving all these years.

Costa Rica is not a country that comes to mind when thinking about cocaine or cartel activity. Because of its geographical location, Costa Rica is a bridge similar to Panama, connecting Colombia and the route north. Despite attempts by the United States government to make it appear that Colombia’s drug and cartel days have passed, Colombia is still the largest producer of cocaine. A high percentage of cocaine trade that makes it out of the South American country passes Costa Rican air, water, or land space.

Costa Rica authorities seized a recorded 57 tons of cocaine in 2020, up 56% from the previous years. Small submarines have been intercepted trucks carrying local trade, but the most common are airdrops. This is a small package dropped into the forest to be picked up by local couriers and transported via a small single-engine plane onto its next destination.

For these airplanes to take off, jungle airstrips are needed. Most often, valued trees are stripped of their bark around the base to dry out and justify cutting them. This dictates where these airstrips are located. When these illegal airstrips are created, there are multiple sources of revenue to be made, one of which is by the courier, but the other is through the removal and selling of the trees.

Parajeles told me about a recent situation that occurred towards the end of 2021 where an illegal logger clearing trees for an airstrip did not account for the entire money earned to the cartel. He paid with his life. He was beaten and hung in his own bathroom. Parajeles was one of the first people made aware of what happened. He arrived with his camera and took photos of the scene, including the body. He showed the raw images and told me the story of how he has been threatened by cartels and their impact on local environmental efforts.

When I asked Mr. Parajelis what he thought the future would bring or what might need to change, his response was as direct, “My generation; the older generation must parish, my generation is teaching the young generation this lifestyle.”

Parajeles told me how the locally sponsored government program Fundacion Neotropica had a program that reached out to rural families and children to teach the importance of ecology and protecting wildlife. The uncles and grandfathers would take the same children out hunting as soon as the program ended- not out of defiance, but more as a way of life. It’s what they knew, and it’s how they bonded. Parajeles knew this because they were his neighbors.

As mentioned in a previous article A Peoples History Of Hunting in Costa Rica, the story of the poacher or hunter is a complicated one.

Parajeles, passion, bravery, and fearlessness are admirable. It’s challenging to know that this is happening in a globally known country like Costa Rica. It’s not to criticize Costa Rica’s efforts and environmental legislation in some respects, and they are leading the charge in how humans interact with the forest. Still, stories like this are reminders that we have a long way to go.

Lastly, what stood out to me was something that Parajeles stated, “I did not know what an environmentalist or ecologist was, I simply knew right from wrong, and that our existence and future is not possible without the animals and the forest.”

Founder of Grow Jungles