Home » Conservation » The History and Impact of the United Fruit Company in Costa Rica

Everything we see on the grocery shelf has a story. Some of those stories are more dramatic than others. Bananas are one of those fruits that most of us have bought by the bunch since childhood, but the history of this tropical fruit may give you a reason to pause before you purchase the next bunch.

Brief history

Bananas have been a staple for people living in the tropics for generations. But in 1870, Captain Lorenzo Dow Baker bought some bananas in Jamaica for one shilling and sold them in Jersey City, in the United States, for $2.

The promise of significant profits caught the attention of railroad and steamship barons from Boston. Captain Baker formed a partnership with Andrew Preston, and together they formed the Boston Fruit Company. The company also owned the largest steamship private fleet globally, known as the Great White Fleet. (1)

Steamships could get the bananas from the tropics to buyers in the north, but they soon saw the need for expansion in those Central American countries.

Boston Fruit Company proposed a merger in 1899 with Minor C. Keith, who owned three banana companies with extensive holdings in Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia. Keith was involved in producing, transporting, and marketing bananas, sugar, cocoa, abaca, and other tropical agricultural products. But most important was the fact that he owned an extensive railroad system in Central America and Columbia. (6) With this new partnership, the United Fruit Company was born.

By the mid-20th century, the company owned over 600,000 acres in Central America and the Caribbean, giving them immense control over local politics and national economies. By 1930, United Fruit Company controlled 90% of the banana import business in the United States and was the largest employer in Central America. The European market soon followed.

Over the next few decades, they bought up most of their competitors in Central America. (5)

The United Fruit Company could be described as a monopoly in certain regions known as the Banana Republic, including Costa Rica and Honduras. (2) They developed strong relationships between the Columbian and American governments by building their railway system.

As more foods were being processed, the company saw the need to diversify to meet demand. New items were hitting the shelves, such as canned pineapple and dried fruits. In 1970 United Fruit Company merged with AMK Corporation to form United Brands Company. That conglomerate became Chiquita Brands International in 1989.

Costa Rica

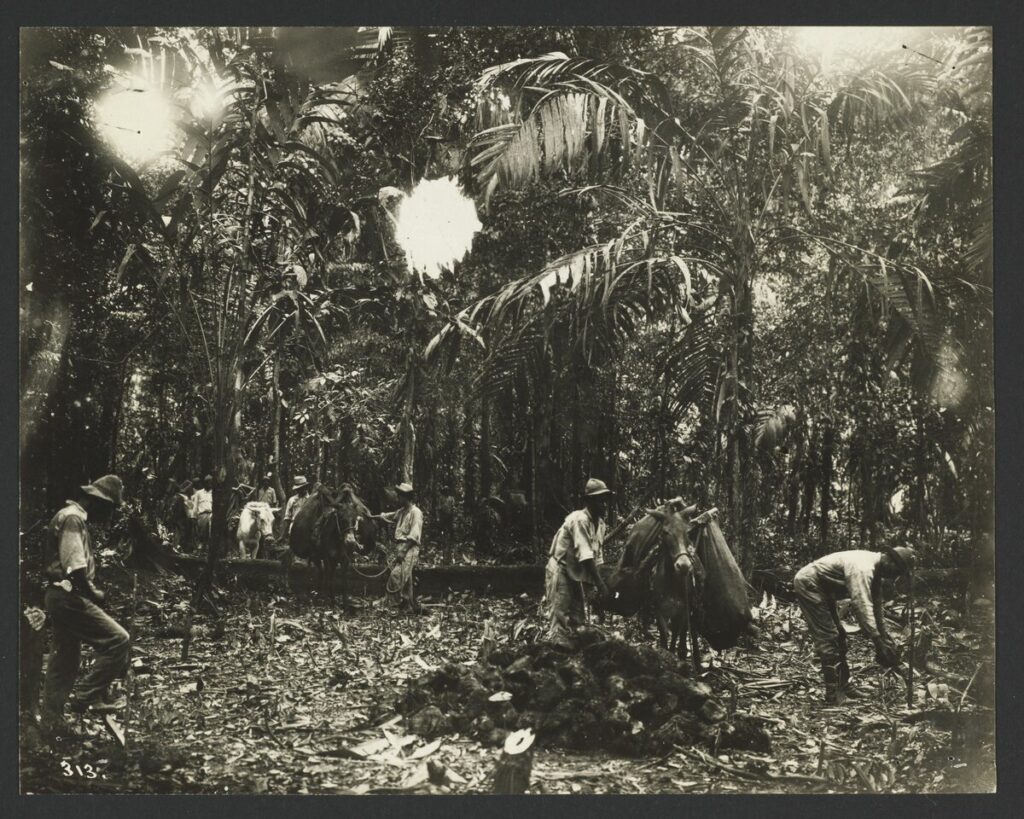

As demand rose, the United Fruit Company saw the need to expand to the Southwest regions of Costa Rica in 1937. This was an area of minimal human habitation and was considered a primeval wilderness.

The company’s goal was to get crops to the coast to be transported to international markets. This required additional rails to be laid.

It takes a lot of hands to build a railroad. Local communities could not fill these jobs, so United Fruit and the Costa Rican government imported labor by the thousands from China, Jamaica, Cape Verdi Islands, and Italy. That stretch of the railroad was completed in 1940. (3)

While the message from the company was that they were providing good jobs and bettering their local economies, it came with trepidation.

They did build needed infrastructure, but the company manipulated what roads were to be made. They feared that building government roads would take away business from their profitable rail system.

The reality was that employees and overseas investors benefited from the company’s profits more than the residents.

The Great Banana Strike of 1934

While the company promised economic improvements, the workers were suffering from low wages and other exploitation.

In 1934, over 100,000 workers from 30 separate unions declared the Great Banana Strike.

It all began on August 4th with one man, Carlos Luis Fallas, representing the Atlantic Workers Congress. He presented a list of requests to United Fruit Company’s management, which they denied, and a strike followed.

The strike affected the largest area ever recorded, from Turrialba to the Panamanian border.

Earlier in that decade, the exporters had taken a big hit during the depression. At that point, the company left banana production to local plantations. This resulted in poorer working conditions and fewer available jobs.

By 1934 workers were demanding an eight-hour workday, overtime pay, and cash payment instead of the coupons they were using that could be used at designated police stations and health services. (6)

The strike lasted through August when the Costa Rican government and local businesses accepted the requests. This gesture temporarily stopped the strike.

United Fruit Company did not agree to the requests, resulting in the local farmers withdrawing from the agreement. This resulted in violent repressions incited by the company. Several workers, including Fallas, sought refuge in the jungle.

Workers did what they could to fight back. They burned and destroyed some of the company’s shipments and products. This prompted the company to agree to minimum wage, adequate housing to be paid by the employer, and first aid kits. Both sides had to compromise.

In the end, the strike helped consolidate the labor movement. Many of its participants later became leaders in social reform processes in the 1940s, leading to the Social Guarantees and the reformist State of Costa Rica. (4)

Growth comes at a cost

As expansion grew across Costa Rica, the company brought its American cultural understanding of what they saw as a frontier environment. They considered the landscapes as ‘uncivilized’ and in need of improvement, using descriptions of “unimproved, threatening, and resistant” to Company designs.

They came in and Americanized Nature, much like what was done during the western expansion of the United States.

United Fruit drew on these historical interpretations of the environment and approached the task of plantation construction, or environmental transformation, by utilizing this historically-informed – and fundamentally American – cultural lens. Characterized by dense jungles, high humidity, heavy rainfall, and extreme temperatures, tropical environments posed a series of threats to the imposition of Company designs. (7)

As the company made way for the railroad and more plantations, they removed dense underbrush, cut down trees, and excavated intricate drainage systems to build plantations and the thousands of dwellings that go with them.

Workers suffered from malaria and yellow fever as they plowed their way to the coast. The company did provide clean water, screened living quarters, and health care because mortality and morbidity rates threatened production. (7)

The United Fruit Company was given a significant land concession, equivalent to almost 9% of the landmass of Costa Rica. It was the only employer from 1899 until it left the country in 1984 due to anti-trust laws from the American government, labor conflicts, soil exhaustion, and higher production costs. But the impacts are still there.

Once the land is cleared for a banana plantation, the fertility of the land diminishes greatly. This results in a vicious cycle of banana producers needing to continually expand their fields due to the declining fertility of the soil.

Monocultures also keep plants from developing immunity to disease, which then results in the application of agrochemicals. Fungicides and insecticides are applied as many as 40 times per year. These cancer-causing chemicals threaten plantation workers as well as surrounding areas.

Biocidal agrochemicals were used in large-scale amounts in Latin America by the United Fruit Company between 1938 – 1962. Thousands of employees applied these chemicals over those years. (9)

These chemicals eventually seep into the water table and into aquatic systems, endangering many types of wildlife and humans.

When lands are planted in a monoculture crop, it tends to produce a lot of sediment and agrochemical runoff that makes its way to sensitive coral reefs off the coast of Costa Rica. Extinction threatens tortoises and manatees as this runoff kills the algae they rely on for survival. (9)

Deforestation, mono-crop plantations, and chemical use leave a soil so devoid of nutrients that it is impossible to grow any other vegetation, killing the region’s biodiversity.

Founder of Grow Jungles