In the dense brushlands of South Texas, among the thorny mesquite, cactus patches, and winding creeks, a ghost moves silently. With golden eyes and a rosette-covered coat, the jaguar (Panthera onca) is not only the largest cat in the Americas but also one of its most elusive. While today jaguars are more commonly associated with the Amazon Basin or the jungles of Central America, their historical range once extended deep into the southwestern United States, including Arizona, New Mexico, and yes—Texas.

For centuries, jaguars roamed freely across the Lone Star State. But their presence today is more myth than reality, and their future hinges on whether humans will allow them to reclaim a land that was once theirs.

The story of jaguars in Texas is one of memory, disappearance, and potential rebirth. Historical records and accounts from settlers, ranchers, and naturalists confirm that jaguars were once found as far east as Louisiana and as far north as the Grand Canyon. In Texas, they were documented as early as the 1800s.

One of the earliest recorded jaguar killings in Texas occurred in 1825 near the Nueces River in what is now Nueces County. The area, characterized by a mix of prairie and dense brush, was ideal jaguar habitat. Between 1850 and 1900, accounts of jaguar sightings and killings became more common, particularly in South Texas. Counties like Duval, Brooks, Kenedy, and Starr recorded multiple instances of jaguar activity.

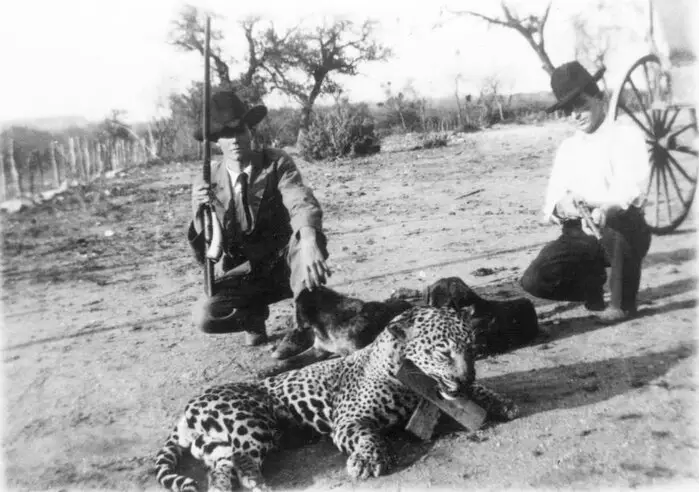

In 1903, naturalist Vernon Bailey documented a jaguar specimen in Cameron County near Brownsville. That same year, a rancher reported killing a large male near the Rio Grande. These reports were not isolated. According to a 1933 compilation by Frank C. Hibben, over 50 jaguar sightings and killings had been reported across southern Texas by the early 20th century.

But the tide was turning.

By the 1940s, jaguar populations across the United States were in sharp decline. Habitat destruction, hunting for pelts, and federal predator control programs decimated the species. In Texas, ranchers—concerned with livestock safety—often shot big cats on sight.

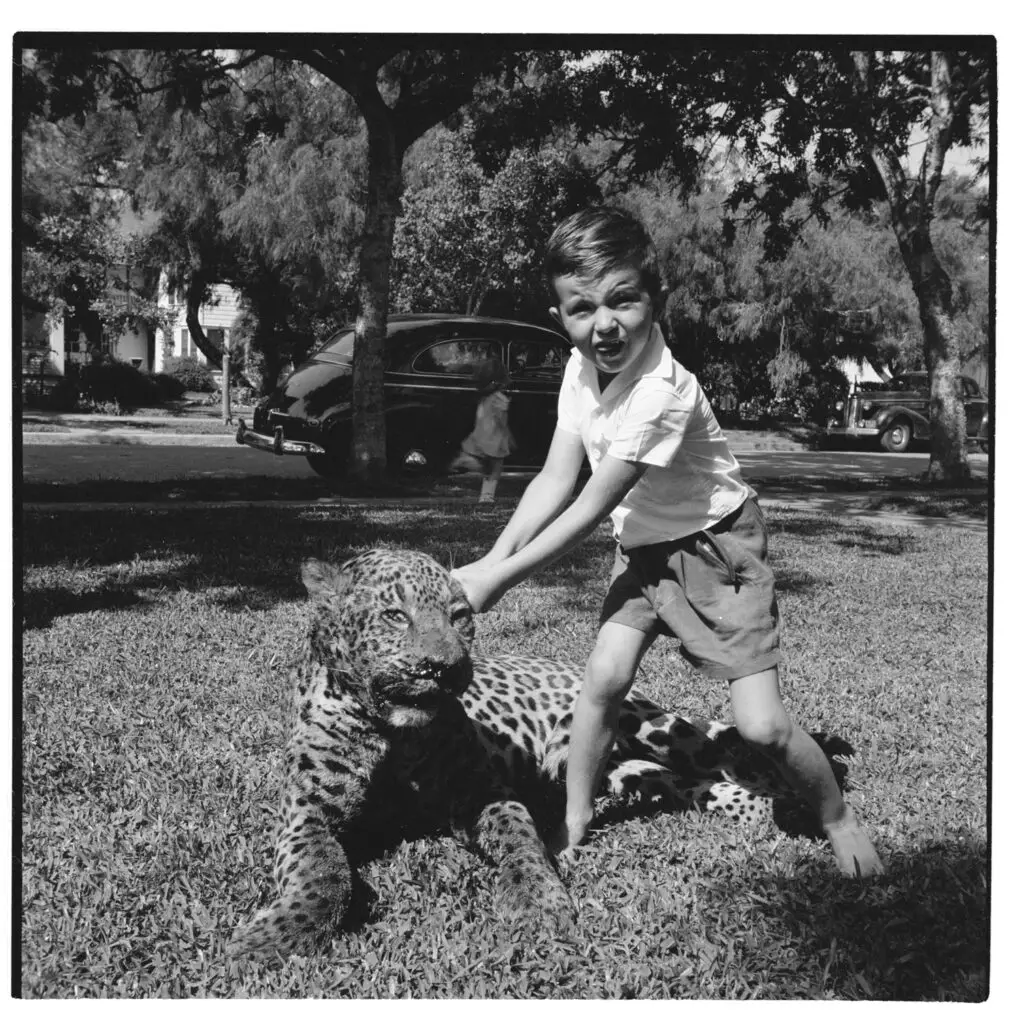

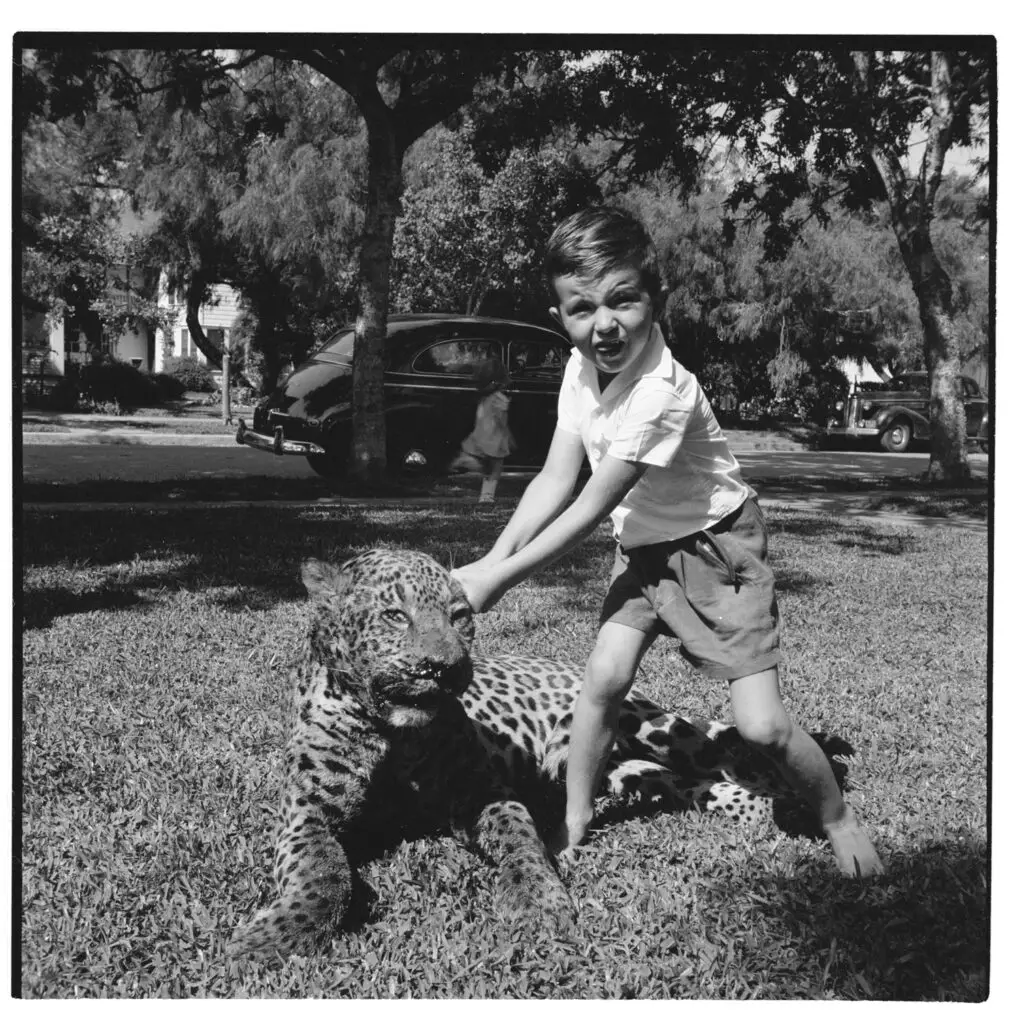

The last confirmed jaguar in Texas was killed in 1948 in the Armstrong Ranch, Kenedy County. The 180,000-acre ranch is part of the South Texas Brush Country, a region once teeming with wildlife, from ocelots to black bears to jaguars. The Kenedy County jaguar, a male weighing around 200 pounds, was killed by a local rancher and its pelt preserved—one of the few physical pieces of evidence that jaguars roamed the region in the modern era.

After 1948, they were considered extirpated from the state.

Across the border, however, jaguars continued to persist. Northern Mexico—especially the Sierra Madre Occidental and the subtropical forests of Sonora and Tamaulipas—remained a jaguar stronghold.

In the 1990s, conservationists in Mexico began to track jaguars using camera traps and telemetry. They discovered that some male jaguars were still dispersing north, sometimes covering over 100 miles in search of territory and mates. In 1996, a male jaguar named “Macho B” was photographed in southern Arizona, just 60 miles from the Texas border. He would become a symbol of the species’ tenacity, living in the Arizona mountains for 13 years before being euthanized due to health complications in 2009.

While Arizona gained national attention for its jaguar sightings, Texas remained silent. But biologists were watching closely.

In 2011, researchers from the University of Arizona and Northern Jaguar Project suggested that South Texas, particularly the Tamaulipan Thornscrub ecoregion, still contained sufficient habitat to support jaguars. Studies showed that a minimum home range for a single jaguar could be up to 50 square miles, and vast ranchlands in Texas still offered such expanses—largely intact and relatively undisturbed.

The Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge, a 90,000-acre protected corridor of thornscrub and riparian forest in Starr, Hidalgo, and Cameron counties, was of particular interest. Could it one day become a jaguar sanctuary?

Although no confirmed sightings have occurred in recent years, whispers continue. In 2013, a rancher in Brooks County reported spotting a large, spotted cat at night, though no photographs or tracks were ever found. Game cameras installed for ocelots in the area have occasionally picked up indistinct feline shapes, leading to speculation.

Then came a breakthrough—though not in Texas.

In 2021, a jaguar was caught on camera in Tamaulipas, Mexico, just 20 miles from the Texas border. This fueled discussions about natural re-colonization, particularly if wildlife corridors could be protected between Texas and northern Mexico.

And then in 2023, a more compelling piece of evidence emerged: scat samples collected in South Texas as part of an ocelot study revealed partial DNA matches to Panthera onca, the jaguar. Though inconclusive, the findings reignited interest in the idea that jaguars might already be slipping back into Texas undetected.

The possibility of natural recolonization faces a major obstacle—the border wall.

Constructed in segments since the early 2000s and accelerated in 2017–2020, the U.S.-Mexico border wall has become a physical and ecological barrier. Jaguars, which rely on wide-ranging movements for territory, are effectively blocked from moving north. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, over 650 miles of wall were constructed in the Southwest, including in areas adjacent to key jaguar corridors.

In Starr County, Texas, construction bisected habitat that could serve as a vital passage for jaguars and ocelots alike. “It’s not just a wall,” says Dr. Alejandro Ceballos, a jaguar expert from Mexico’s National Autonomous University. “It’s a knife through the heart of the ecosystem.”

In response, some conservationists are calling for more proactive strategies. One bold proposal came from the Rewilding Institute in 2022: reintroduce jaguars into the wilds of South Texas. Using a model similar to the wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone, jaguars could be bred in captivity and released in protected or semi-protected lands, such as the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge.

But the idea is controversial. Ranchers, already wary of predators due to frequent livestock losses from coyotes and feral dogs, fear economic repercussions. The Texas Wildlife Association has argued that landowners should be part of any future discussion before reintroductions are attempted.

Still, public opinion is shifting. A 2024 survey by Texas A&M University found that 61% of Texans supported jaguar reintroduction if it were shown to help restore ecosystems and biodiversity. Among respondents under 35, that number rose to 74%.

In early 2025, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced a new initiative: the Borderlands Big Cat Recovery Program, backed by $15 million in federal and private funds. The program focuses on three pillars:

Expanding camera trap networks in South Texas to capture visual evidence of big cats, especially in brush-heavy counties like Kenedy, Starr, and Willacy.

Landowner incentives for maintaining or restoring habitat corridors crucial for ocelots, jaguars, and other wildlife.

Cross-border collaboration with conservationists in Tamaulipas and Sonora to build ecological continuity from the Sierra Madre foothills to the Rio Grande.

Texas Parks and Wildlife also launched a citizen science app called Jaguares del Sur, enabling locals to report big cat tracks, sightings, or game cam footage.

These are among the last verified or strongly corroborated sightings or kills of jaguars in Texas:

1948 – Kenedy County: Last confirmed kill on Armstrong Ranch, male jaguar.

1946 – Brooks County: Shot near Falfurrias after livestock loss.

1942 – Duval County: Spotted and killed near San Diego.

1938 – Hidalgo County: Seen and hunted near the Rio Grande.

1935 – Zapata County: Body recovered on eastern bank of Falcon Lake.

1933 – Cameron County: Collected as a specimen by Vernon Bailey.

1928 – Webb County: Large male killed near Laredo by trapper.

1923 – Starr County: Shot outside Roma after rancher sightings.

1919 – Nueces County: Witnessed near the Nueces River.

1911 – Jim Hogg County: Male jaguar killed near Hebbronville.

These sites form a rough crescent across the South Texas brushlands, suggesting the area’s importance as both historic range and future recovery zone.

Given the right conservation conditions, these five sites stand out as the most promising for reintroduction:

Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge (Cameron County)

Nearly 100,000 acres of prime thornscrub, already home to ocelots and other rare species. Excellent federal oversight and minimal human encroachment.

Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge (Starr, Hidalgo, Cameron Counties)

A patchwork of protected corridors along the river, connecting potential rewilding areas with Mexican jaguar populations.

Kenedy Ranch (Kenedy County)

Over 200,000 acres of privately owned, low-disturbance land. Critical due to its historic role in jaguar territory.

El Sauz Ranch (Willacy County)

Managed by the East Foundation with ecological restoration goals; supports prey species and other carnivores.

Big Bend National and State Parks (Brewster and Presidio Counties)

Though less optimal due to desert terrain, they offer vast, rugged wilderness and potential future range expansion from Mexico’s Sierra Madre.

For now, the jaguar remains a ghost—its memory etched in dried pelts and dusty ranch records. But nature is patient, and the landscape remembers. If people, science, and policy align, jaguars may yet return to the place where they once thrived.

The question is not whether jaguars belong in Texas—they always have. The real question is whether we will welcome them home. And if we do, we might just find that we’ve restored something greater than a species—we’ve restored a piece of Texas itself.

More articles on the topic of Jaguars in Texas:

London, Texas Jaguar – 1909

Rio Grande Valley Jaguar – 1946